Fencing Considerations, Part two

The intent of this article is to look at the big picture of your horse farm’s features and then to consider fencing, gating, and corral features that could be installed to make it safer and more functional. Safer for whom you may ask…..well, safer for you and your family members, for the horses, and boarders who spend time there working with their horses and taking lessons. But also of importance is the safety of your neighboring property owners because loose horses can cause damage to crops, punch holes in well-manicured lawns, and frighten and injure people who are not used to livestock and / or may simply be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Of course, it is critical also to consider the safety of people passing by on roadways and along greenways and trail systems that border your land.

No one wants their horse to get hit by a car, and no one driving a car wants to hit an animal. Should you have a loose horse incident / liability claim, in rural areas of agricultural states the question will likely be posed as to how often a horse escapes from your property. If it happens once in 3 or 4 years, it will not seem as bad from a legal standpoint as if they get out 3 or 4 times a year.

As mentioned in my previous article, first check on local, county and state laws relating to fencing requirements for large livestock. If your property is near or abuts up to a state or federal highway or freeway, stronger rules may apply. Non-ag states and highly populated areas may have higher standards that could affect the outcome of a claim. Granted, there are situations in which horses getting out of pastures would be difficult, if not impossible, to avoid. One example may be when a severe storm takes down a very substantial fence in the middle of the night, after which the horses panic and escape down the road. As a horse business operator, you will be expected to take reasonable care to contain your horses, and what constitutes “reasonable care” can depend upon the area or state in which you reside, and according to the seriousness of the human injuries and property damage incurred.

In theory, if a horse farm owner has 100 acres to work with, the largest fenced tracts will be the most outlying pastures and fields and these will take up approximately 60% or 60 acres around which will be the property perimeter fence. Let’s refer to the most outlying fields and larger pastures as the 3rd Tier of the operation. The most interior building site we shall call the 1st Tier. The building site may require 10% of the land or ten acres, which is the center of activity. Tier 1 will include the smallest fenced enclosures such as exercise paddocks; outdoor arena; training pens; and corrals, catch and holding pens. These smaller enclosures will be closest to the center of activity….close to and a part of the stable facilities. The types of fencing used for these 1st Tier enclosures will depend upon function, looks, and how they will be used. The 2nd Tier will make up the approximate 30% balance or 30 acres. The 2nd Tier will often be used for the medium-size grassed grazing pastures, and often lie in between the larger pastures and fields, so lanes and field roads may be used to reach the 3rd Tier from the 1st Tier.

However, having 80 to 300 acres or more for a horse operation these days is becoming more unusual. Many horse operations are built on 25 acres or less, and may be only 1st Tier types having no grazing pastures and large turnout enclosures. 1st Tier stable owners will need to buy hay to feed year-around. 50 acres may allow for a 1st and 2nd Tier stable that allows some grazing, some hay production, but still require hay to be purchased for the non-growing season, colder months. 3rd Tier stables should be able to raise their own hay and have longer term use of pastures. With enough land, pastures and large paddocks available, one can rotate pasture and paddock use, make hay off the highly productive grasslands before pasturing, all of which is good for the land, and generally healthier for the animals.

Most operators purchase a site with some adaptable buildings and fencing; then over several years will build and design the fencing and new buildings according to what was originally there. If one can afford to buy a nice 100 to 200 acre bare tract and design and construct the building site with 2nd and 3rd tiers, from scratch, an architect could be hired to design the most perfect, beautiful and safest fencing and facilities. But that is not how most of us start out. Most people start out with partially built property, no design plan and a limited budget. None-the-less, all have an opportunity to design ongoing improvement projects thoughtfully with a view toward function and safety.

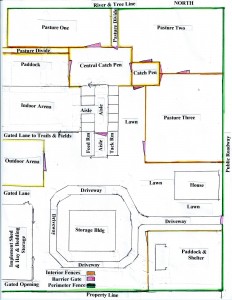

To facilitate the discussion, I’ve included a rough drawing that is similar to my own 8 horse boarding, training and lesson stable with outlying grain and hay fields. The horse part of the 122 acres occupies only 20 acres and the perimeter fencing encompasses just that area as that is the part of greatest concern for safety and function. The pastures and paddocks each have multiple uses. I have 3 square training pens that are 40’ x 40’, 50’ x 50’ and 60’ x 60’ and an outdoor arena that is 66’ x 132’. While many people today use round pens for training, I like square pens because I use the corners for so many techniques. The training pens also function as isolation, catching and holding pens. I like the option of different sizes to accommodate the size of the horse and its stage of training. There are times when I want to keep a horse and student very close to me because I want better control and concentration for each of us, and the 40’ pen is perfect for that, but it is rare that I consider that pen large enough to canter in. Two catch pens and two second barrier gates in two barns were installed for more function and safety for boarders and horses. The original wood post and cattle panel fencing is almost totally converted now to free-standing galvanized pipe. I budget in and buy some panels every year.

My aging parents used to enjoy taking care of the horses. Around the time they turned 65, I became concerned about their safety in leading the horses in and out, and I didn’t want for them ever to have to chase loose horses. Thus began the process of making a design plan for moving horses into and out of pastures more safely, and considering carefully what would happen if a horse escaped at certain locations, and where the horse could go if that happened. As I asked that question from many different places around the stable and in the barn, it became clear that I needed to install barrier gates and second barrier fencing, so that if horses escaped from their stalls and down the alley, they could not exit to the “wild-blue-yonder” part of the yard, or get into feed storage areas, or run across or down the bordering county road. As the fence and gating design has developed over the years, I found multiple uses for the enclosures that were added. Today I am really happy with the safety and function of the place.

After reading this article I suggest wandering your property with a notepad to drawn designs, and ask yourself these questions at various points inside and outside the buildings: 1) If a horse escaped at this point, where could they go? 2) Where could I put a gate, catch pen or another fence line to keep horses contained and controlled? 3) What fencing and gate features would make the place safer for boarders getting horses from the pastures and bringing them into the barn; and make their way safer to the trails, training pens, and riding areas? 4) What such added features would make the feeding and caring of the horses by staff easier, more efficient and safer? 5) Could the new feature serve other purposes? 6) By prioritizing which features are most important to change, and keeping this year’s budget in mind, which features should be constructed first?

Gate and Stall Latches: Think carefully about your gate and stall door latching systems. Some horses are smart at figuring out how to not only let themselves out, but also how to let out other horses, which has the potential to be disastrous. The behavior usually involves wanting food or seeking novelty to avoid boredom. I strongly believe in a double latching system and the use of fairly beefy chains, hooks and snaps in addition to whatever latch the gate or stall door comes with when purchased. If the chains and snaps look “wimpy” to me, I will change them to something stronger. One should never underestimate the power of a horse….keep in mind that they are big and strong and when on the move or pulling back, the strength of your gates, ties, and fencing will be tested. The latches should be easy for people to open, but not easy for horses to figure out. If boarding horses, be sure to carefully show and explain your gating and latching system and rules to boarders. Explaining the safety reasons for why something is done usually helps people remember.

Be sure to explain the danger in not giving the horse enough room to get through the gate or door, as not only can the gate or door be damaged, but a horse can become severely injured from trying to blast through an opening too small for it. Also provide braces or ties at gates to keep the gate in place when letting horses in and out, so that the wind does not blow the gate shut when a horse is moving through. I know of horses that have had not only severe lacerations, but internal injuries as well because a gate slammed against them as they walked through. The horse’s panic tendency will be to push into it instead of backing up. But either direction they try to move can cause injuries that can involve the handler being in the way and injured too.

Also, make your boarder’s family members, and staff members understand that any time they are going through a gate with a haltered or bridled horse, to lead the horse wide around the fence and gate. A horse is prone to wanting to rub their heads against the entry gates and posts while waiting to be led through. Should the halter or bridle get caught and the horse pull back, head and mouth injuries can result and the horse can remember the occurrence for a long while. A broken $350 bridle will not make anyone happy either.

As I get into some simple fencing features, please take a look at the hand-drawn horse farm layout to follow. I want readers to consider five kinds of features: Perimeter Fencing, Interior Cross-Fencing, Barrier Gating, Pasture Dividing Lanes, and Catch-Pens (corrals).

Perimeter Fencing: In Europe some horse “fences” are made of solid, old, tall non-mortared stone walls, or thick, impenetrable thorny, spiny living hedge that may have been serviceable for hundreds of years. Yet, today of the 69,926 miles of dry stone wall in England alone, only 13% is stock-proof. If a portion of the hedge dies, or if part of a stone wall crumbles, the owner might have to fill the gap with another type of fencing. Stone and hedge fences are not seen often in the U.S., but are examples of how even the most formidable fencing systems need regular attention and care to keep animals in.

Perimeter fencing is that which surrounds or encircles the entire property. One of its purposes is to mark the property boundaries between landowners. It may also be used to prevent or make entry into the property less easy and attractive, especially if the fence is strong in appearance and marked with no trespassing signs. In the case of a horse operation, its purpose is to keep animals from escaping into surrounding land, fields, and roads owned and controlled by others. Perimeter fencing often runs along public roadways, greenways and streams. Because of its importance as the final barrier to keep animals in, perimeter fencing should be the strongest and tallest of your fences. It may be marked as such by signs being posted along the fence that tell who owns the property, and that it is private. If part of the fence is electrified, some states or locales require they be marked as such so people are warned before they touch them.

I wish to make one important observation about perimeter fences installed around trailer parking areas for events where horses are loaded and unloaded, and tied to trailers or tie rails for long periods of time. Horses frequently get scared and run away from handlers or break free from the tying apparatus at such events. I know of several severe liability claims that could likely have been avoided if perimeter fencing enclosed the area even if gated entrances were open for a flow of traffic. Most of the claims involved severe injuries and / or death of car drivers and passengers that crashed into a loose horse in the road.

One unusual incident involved a trail ride group that set up camp on a vacant lot beside a restaurant business parking lot. The restaurant did not have any ownership, involvement with, or control over the field used by the trail ride group. The restaurant was not involved in any way with the decision to let the group stay on the bordering property, nor did the restaurant own or keep livestock at the premises. At one point a horse on the vacant lot became frightened, broke free, and ran blindly off across the restaurant’s parking lot and straight into an open car door just as an innocent passenger was getting out. The force of the horse hitting the door slamming it against the passenger’s body was so great that she received severe life-long debilitating injuries. Had there been perimeter fencing around the vacant field, this incident would likely never have happened. The restaurant was drawn into the claim because the incident happened on its property. But, who should have been responsible for putting up a boundary fence? The restaurant or the empty lot owner? Keep in mind that generally liability for such an incident rests primarily on the person having the immediate care, custody and control of the horse which got away. In other words, who was responsible for caring for and controlling the horse at the time?

When considering the layout of your horse operation, think about what natural or manmade features just outside the fencing perimeter, as this may help decide the best type of fencing to apply there. In the example diagram, a river and tree line lies along the North side of the property. This may be considered a good natural barrier. However, if horses get out, they can wade or swim across rivers, and they can wander along till they get to and into a public roadway or public trail. A flimsy fence through a wooded area can be hard to maintain because of fallen trees and branches that can land on a fence line. Also, these days many soil and water districts have rules about maintaining buffers between fences and natural streams, rivers, and drainage ditches, so you may need to hold your fencing back a specific number of feet from the waterway.

In the diagram, a public road runs along the east side of the property, and this fence line is a high priority for strong fencing of adequate height. To the south is a property line between land owners, and to the west lie fields and riding trails owned by the horse farm operator. Carefully consider the location of gates in perimeter fences and if you need to install them at all. For some reason, gates along roadways catch the eyes of people passing by and some might consider opening the gate as a prank, or to enter and touch the horses. Of course, pranksters and vandals can cut wire as well, but it seems that the gates sort of invite entrance.

Ideally we never want horses to get away from the property, into the road, or in with horses they should not be with because of gender or personality conflict. As I mentioned in the last article, there is no such thing as perfect fencing, but some fences create a better barrier than others. In the last article I discussed fencing types and heights.

It should be noted that some companies selling electric fencers advise that their product is not suitable for perimeter fencing. Keep in mind that electric fencing and fencers can come down in a storm, and flimsy fencing can be taken down by deer or panicking horses. Every fall I put up temporary highway department grade 4 ft orange snow fencing. It is bright orange, highly visible, and when attached to buried posts set every 12’, it is sturdy enough to stand in a hard-blowing wind, and serve its purpose to keep snow from drifting into places not wanted. Yet, almost every year deer will run through it after dark a couple times over a 5 month period. As I look around in my travels, I like to see what people are using for livestock fencing. I know that my snow fencing is stronger and more visible than what is often used for horses and cattle and what is considered acceptable for many rural areas. I often see a single or double-strand of electric fence running within a couple feet of a roadway. It concerns me that people will take on the expense of buying, feeding, and caring for horses, but skimp on the type of fencing they use to enclose them.

Interior Cross-Fencing: Basically, when a property is cross-fenced, it means that there is a perimeter fence around the entire property line that is divided up into several pastures, and paddocks by “cross-fencing.” Cross fencing allows options for livestock control and containment, some of which includes pasture rotation where one pasture or field is grazed while another is resting and growing back, or allows for separation of livestock that should not be together. It is extremely helpful to have gates between pastures and paddocks to make it easier to move horses around, and also for entry with a tractor and machinery.

Depending upon the size of the pastures and paddocks, and the types of animals one wants to separate, interior or cross-fencing may be a grade-step down from the strongest, tallest perimeter fencing. Yet, if keeping horses owned by others, or stallions separated from other horses, or if containing especially big horses, short horses, mares and foals, jumping horses, race horses, wild horses; all these must be considered in the types and heights of cross-fencing used.

I wish to mention again that barbed wire is not suitable for horses. Some people will take a chance and use barbed wire on large pastures that are used for both cattle and horses. While horses may do all right in a well-constructed, maintained barbed wire fence on a large pasture tract, barbed wire is not desirable or safe for horses. Barbed wire is best used for thicker-skinned cattle. I’ve seen some very serious injuries happen to horses that get caught in and tangled up in barbed wire, or that run against and along a barbed wire fence. It isn’t worth taking the chance.

Pasture Dividing Lanes: Higher-end horse operations with a substantial financial resources and acreage, such as Thoroughbred breeding farms, often build dividing lanes. A dividing lane is a long fenced narrow “run” of a width between 6’ to 14’ between and separating pastures or paddocks. First and foremost, a dividing lane keeps horses from playing and fighting over their fences because they can’t get close enough to touch each other. The separation is a buffer zone that helps keep horses from becoming injured. While the average horse operation may find it impractical to build dividing lanes because of cost and land use, we can use them in certain areas to not only fulfill the purpose of keeping breeding stallions away from other horses, but also to allow for riding and tractor lanes that provide easy entries to outlying riding areas, trails, fields, and back pastures. The lanes can be used to move a group of horses from pasture to pasture by just driving them down the lane through gates into the pasture located along the lane. A lane can also be used for training, such schooling horses over a series of jumps or cavaletti on the straight-away (“a jumping grid”). The lanes could be cross-gated at both ends and even in the middle for safety and horse movement purposes.

Catch-Pens (Corrals): Catch-pens are most often used for control of and loading of cattle and horses. The catch pen allows for bringing a horse or horses into the smaller enclosed area so they are easier to catch or separate from the herd. These containment areas are usually enclosed by tall, sturdier fencing such as board or pipe rails.

A catch and holding pen that has gate openings to two pastures, and a third for entry into the barn .

Adding catch pens to your horse operation design can add safety for both people and horses, and the pens can double for use in close-up training work. A catch-pen is usually between 30’ x 30’ to 60’ x 60’ square. The pens can be rectangular and may be round or octagon shaped, depending upon how they will be used. It is nice to have corners as they sometimes help to catch or contain a horse. The single catch-pen can be built close to the interior gate opening of a pasture and serve that single pasture or large paddock. However, catch pens can also be built as a central smaller enclosure with 4 to 6 gates that lead out to larger pastures or paddocks.

Example of double barrier gates that can also be used as a temporary catch and holding pen for safely removing one horse from a herd. It consists of two gates at the end of a 3-sided shed serving a pasture containing several horses. The two gates used together provide a 9′ x 13′ containment area.

Second barrier gate across an aisle that closes off the stall area of a stable. When closed, loose horses can’t run through the barn and into an open area that leads to a roadway.

Barrier Cross-Gating: Barrier gates are installed to close across barn aisles or just behind sliding or overhead doors. They can also be used to close off feed areas. The barrier gates can be closed while letting horses in or out and before shutting down the stable and leaving it for several hours. The idea is to provide one or more barriers to keep horses from getting away and out of the stable into an open area that might lead to a roadway. Depending upon the building, two barrier gates installed about 14 to 30 feet apart can be used as a short-term catch and holding pen for a horse, should it ever be needed. Barrier aisle gates can allow solid barn doors to remain open during hot weather.

0 Comments